“In the philosophy of Heraclitus, enantiodromia is used to designate the play of opposites in the course of events—the view that everything that exists turns into its opposite. . . .”

CARL JUNG (1949)

In the year 1665, England was ravaged by yet another devastating wave of bubonic plague. Businesses and organizations were forced to shut down to blunt the spread of the dread disease. Among those institutions temporarily closed: Cambridge University, where a twenty-three-year-old Isaac Newton was finishing his undergraduate degree at Trinity College. The quarantine forced the young Newton to retreat to his family’s estate at Woolsthorpe Manor, located a safe distance away from the epidemic that killed over a hundred thousand—a quarter of the population—in London.1

For the next year or so, Newton sheltered in place, giving him the solitude and intellectual freedom to explore, uninterrupted, the farthest reaches of his imagination. It was during this period of quarantine that Newton stretched the boundaries of optics, set forth the basic contours of what would come to be known as calculus, and formulated the theory of gravity: “Whilst he was pensively meandering in a garden, it came into his thought that the power of gravity (which brought an apple from a tree to the ground) was not limited to a certain distance from Earth, but that this power must extend much further than usually thought. ‘Why not as high as the Moon, said he to himself, and if so, it must influence her motion and perhaps retain her orbit.’ Whereupon he fell to calculating what would be the effect of that supposition.”2

Newton’s year in quarantine came to be known as an Annus Mirabilis—a remarkable or notable year in history; a year of wonders and miracles, with profound implications for the future. Out of death and misery came Enlightenment.

Fast forward to 2020. As I sat in my home office beginning to write this book, we all seemed to be living through a similarly epic time in history: I was self-quarantined at home (no manor, unfortunately) as the coronavirus pandemic raged on, having already killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.3 Simultaneously, we were in the throes of a precipitous economic meltdown not seen since the Great Depression as well as an unprecedented social uprising over systemic racism and social injustice ignited by the murder of George Floyd—an unarmed Black man killed ruthlessly by the police in the city of Minneapolis in 2020. And looming over all of this were the existential threats of runaway climate change, mass extinction, and toxic inequality which (ironically) constituted the root causes of the immediate crises.

By 2021, as my writing continued, the stock market had roared back, making the wealthiest 10 percent who owned most of the stocks even richer than before the pandemic, perpetuating and even exacerbating class divisions and perceived elite privilege. I then witnessed something I thought I would never see in my lifetime: an actual attack on the US Capitol by an angry segment of American citizens that had lost faith in the ability of the country, and the capitalist system that underpinned it, to deliver what Harry Truman called a “Fair Deal” for people.

Then, in February 2022 the unthinkable happened: Vladimir Putin’s Russia invaded the sovereign nation of Ukraine, igniting a brutal military struggle, humanitarian disaster, and refugee crisis not seen since the Second World War. The combination of the Ukrainian war, supply disruptions in China, and rebounding demand from two years of Covid restrictions precipitated a spiral of inflation not seen since the 1970s, and the prospect of a global recession. Controversial rulings by the US Supreme Court on gun and abortion rights in June 2022 then sparked another round of social unrest and discontent, threatening to tear the country apart. And in the summer of 2023, something never seen before in US history happened—the criminal indictment of a former president—multiple times.

It is entirely possible that this combination of once-in-a century crises and disruptions precipitates a further spiral into social division, authoritarianism, and xenophobia. The storming of the Capitol in Washington on January 6, 2021, served to heat up what was already a cold civil war in the US—and inflame an antidemocratic trend that has infected the entire world in recent years. Witness the ominous “echo-insurrection” that occurred in Brazil in January 2023 after the defeat of Jair Bolsanaro in the presidential election.

But it is also possible that we are in the midst of another Annus Mirabilis—a time that will come to be seen as a turning point, when, as Willis Harmon quipped, there came a “global mind change” and society changed course in a fundamentally positive way.4 Deep change tends to occur in historical moments—punctuation points—when public consciousness cracks open and new ideas can rush in.5 Kurt Lewin famously noted that before transformational change can happen, organizations and societies must first “unfreeze” the conventions, norms, and standard operating procedures that had previously been taken for granted. The cascading crises of the Covid years seem more than qualified to meet this requirement. Could it be that we stand at the threshold of a new age in human—and business—history?

The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung drew heavily upon the ancient Greek philosophers in formulating his groundbreaking theories in analytical psychology. Among his most important insights was the karmic tendency of human emotions to metamorphose into their opposites—what he called “Enantiodromia.” In his Collected Works, Jung described his use of the term as “the emergence of the unconscious opposite in the course of time.” Jung observed that the emergence of new unconscious ideas occurs when an extreme one-sided tendency dominates conscious life; eventually an equally strong countervailing tendency builds: euphoria becomes melancholy; valued becomes worthless; and good becomes bad.6

Perhaps Enantiodromia can help us better understand the implications of the trajectory of the world today: Brexit in Europe, rising nationalism, and the resurgence of strongmen around the world. Failing states, epidemic disease, mass migration, climate change, and fear of terrorism have been driving a worldwide shift toward isolationism replete with border walls and travel bans. Globalization, financialization, and automation have widened the gap between the haves and have nots, resulting in a swell of dislocated communities, people left behind, and a shrinking middle class in the so-called industrialized world. A resurgence of bigotry and white supremacy in America has fanned the flames of domestic terrorism. A nostalgic desire to return to the high-paying factory jobs and mass consumption of old is fueling a rejection of science and denial of global climate change. Many now legitimately fear that these accelerating global trends will inevitably lead to rising ethnic, religious, and racial intolerance; nativism; authoritarianism; military conflict; climate crisis; and environmental meltdown.

But what if all these disturbing trends are actually a blessing in disguise? What if they represent the last gasp of a dying system? What if the coronavirus pandemic forced us out of our complacency . . . and complicity? What if the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, represented an inflection point in history? What if Putin’s brazen attack of Ukraine ends up uniting the world against authoritarianism, bringing with it a rebirth of democratic values? What if we are on the verge of a major shift in worldview that will catapult us toward a truly sustainable future? Remember that the principle of Enantiodromia teaches us that extreme one-sidedness builds up a tension, and the more extreme the position, the more easily it can shift to its opposite.

A Hillary Clinton presidency would probably not have created such an extreme. On the contrary, it would likely have resulted only in incremental improvement to the faltering neoliberal order insufficient to rise to the challenges—rather than deep change. What if our current conundrum is the start of a giant pendulum swing in the opposite direction? What if the rise of Gen Z signals a sea change in our attitudes about climate, racism, social issues, and guns? What if we are witnessing the demise of shareholder primacy and market fundamentalism as the organizing principles of capitalism? What if we are on the cusp of a new age of business and society characterized by tolerance, social inclusion, racial justice, regeneration, and environmental sustainability? Remember: it’s always darkest just before the dawn.

In 1517, Martin Luther posted his “95 Theses” on the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany, challenging the orthodoxy of the Catholic Church and unleashing a wave of religious, political, and intellectual upheaval. The Protestant Reformation was fundamentally a challenge to papal authority—it held that the Bible, not Church tradition, should be the sole source of spiritual authority. In other words, it was time for Christian practice to be driven by parishioners rather than the needs of the high priests and religious elites.

Fast forward to 2018. When Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, issued his first letter to CEOs imploring that companies focus on societal purpose (not just maximizing shareholder returns), it was not unlike Martin Luther’s “95 Theses.” He amplified a wave that had been building for more than three decades—a “capitalist reformation.”7 Indeed, since Fink’s initial letter, the Business Roundtable and the World Economic Forum have both issued formal statements redefining the purpose of business as one that makes a positive contribution to society, not simply maximizing returns to shareholders.8 Certainly, proclamations are not the same thing as real action: recent admonitions about the insincerity of “woke” capitalism—that stated concerns for societal issues by some financiers and corporate leaders are little more than cover for gaining more market power—should not be ignored.9 But perhaps the time had finally come for business to be driven once again by the needs of all stakeholders, not just those of the high priests of Wall Street, CEOs, and the financial elite.

The problem is that business—and business education—tend to be pathologically ahistorical. Most people in companies think useful business knowledge has a “half-life” and that anything older than a few years has passed its expiration date. This attitude is reinforced by business schools where MBA students demand “new” cases and readings, and faculty tend to oblige to keep their teaching ratings high. The result is a profoundly unreflective culture, in which “new” wins out over experience or historical perspective. The truth is that the current state of the shareholder-driven capitalist endeavor has existed for only a relatively short period of time. Knowledge of history, therefore, can be empowering, offering lessons that the deepest understanding of current reality can never provide.

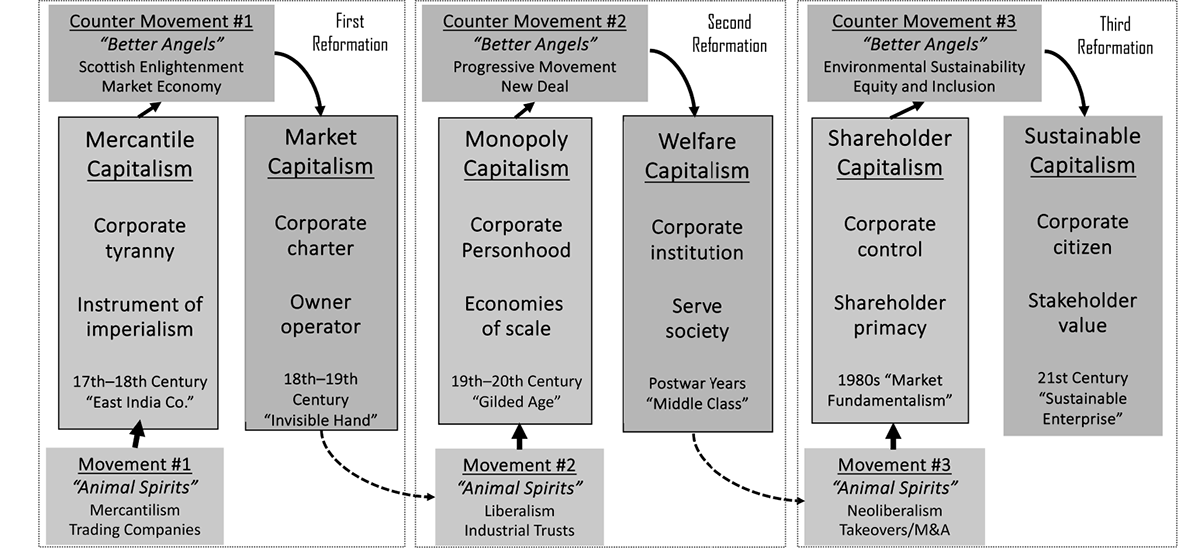

The current movement to remake capitalism is not the first time the economic system has undergone significant transformation. In fact, between the time of Luther and Fink, capitalism has undergone three major cycles of reformation—beginning with the fall of feudalism and the rise of mercantilism in the seventeenth century (Exhibit P.1). Each cycle has been initiated by a movement that propels capitalism to a new stage of development, animated by what John Maynard Keynes described as our “animal spirits.”10 These more primal forces—greed, extraction, lust for power—lead to an extreme, one-sided tendency toward exploitation, concentration of wealth, and degradation of the social fabric and environment. Such excesses then produce a countermovement animated by what Abraham Lincoln described as our “better angels.”11 These more compassionate forces—empathy, mutuality, concern for the common good—then lead to new “reformed” versions of capitalism. Think of it as three Enantiodromia cycles of capitalist reformation, with the third unfolding as we speak.

What becomes clear is that capitalism’s operating system (the “code” that defines how to play the game) and objective function (the narrative myth that sets forth the prime directive—what the system seeks to prioritize and promote) all but determine societal outcomes. Today’s shareholder capitalism, for example, seeks to maximize the returns to a single stakeholder—investors—by maximizing the quarterly earnings growth of companies. As executive turned author Ed Chambliss notes, focusing on returns to a single constituency group while downplaying or disinvesting in others (such as employees, suppliers, customers, and communities) is like trying to balance on a “one-legged stool.”12

But like past cycles of capitalist reformations, tomorrow’s sustainable capitalism aims to expand this logic by defining societal contribution—serving all stakeholders—as the objective function with profitability representing only one of the many necessary prerequisites to achieving this larger end. As Darden School professor Ed Freeman explains, this version of capitalism taps the “power of AND” rather than seeing the various stakeholders’ interests as inherently in conflict—a zero sum game.13

The use of the term “reformation” here also seems apt, given the religiosity and ideological fervor of the crusaders for the various forms of capitalism throughout history. As we will see, this has included passionate belief in such things as Deism, Social Darwinism, and market fundamentalism. Indeed, there is a mythical quality to the rhetoric used by advocates for the various incarnations of capitalism. Witness the use of terms such as invisible hand, general equilibrium, magic of the market, trickle down, economic liberty, and most recently, sustainability and regeneration.

Through it all, there is a certain sense of déjà vu—that which goes around comes around again. Indeed, the first section of the book will make it apparent that many of the challenges capitalism faces today—concentration of wealth at the top, monopoly power, environmental degradation, and toxic levels of inequality—have been confronted before. And while the scale and scope of the challenges we face today may be unprecedented, we can learn from history so, as the saying goes, we are not doomed to repeat it.

Chapter 1, “Capitalism’s Heritage: Extraction Is Not Preordained,” takes a deep dive into the roots of our current predicament. It begins with an effort to understand the origins of the capitalist “mindset,” given that the modern orientation toward progress, prosperity, and science dates back only to the Renaissance and ensuing Age of Exploration. For the first two reformations, I try to identify and distill those elements, events, patterns, and practices most important to the evolution of the capitalist idea. Conclusion? There is nothing preordained about today’s obsession with quarterly earnings and shareholder primacy. Chapter 2, “The Next Capitalist Reformation: Sustainable Capitalism,” then explores the rise of neoliberalism and shareholder capitalism in the 1980s and the countervailing forces that now drive the transformation to what I refer to as “sustainable capitalism.” In essence, the first two chapters provide the detailed narrative to accompany Exhibit P.1. The story is told from an American perspective since, for at least the last century, the US has had an outsized impact on the evolution of capitalism around the world. Indeed, the still dominant model—shareholder capitalism—is largely an American creation.

Chapter 3, “History Rhymes: Enduring Lessons for Today,” then distills the learnings from these past cycles of capitalist reformation and explores their implications for the third reformation—the one that is unfolding now before our eyes. I focus on four enduring lessons from this historical journey: (1) Self-interest is not the same thing as selfishness—by returning to the roots of classical economic thinking, we can develop a more expansive view of what it means to be “self-interested” in business (spoiler alert: self-interest has historically been rooted in the idea of serving others); (2) Managerial stewardship trumps the “principal-agent” problem—by looking at past capitalist cycles, we can identify models for managerial behavior and governance that differ markedly from the caricature of the selfish, shirking opportunist needing control assumed by modern financial economic theory; (3) Monopolies are not markets—even though monopolists still use the language of the price system, it is clear from history that the societal benefits of “market” economies are largely nullified when capitalists are allowed to concentrate industries and wealth; and (4) Reinvestment must take precedence over extraction—by examining the long debate about reinvestment of profits versus extraction of wealth, it becomes clear why the former is essential if the promise of capitalism and the profit motive are to deliver positive societal benefits.

History teaches us that capitalism has been run using very different operating systems in the past, and that such systems are little more than social constructions, premised upon narratives, stories, and myths about the way the world—and the economy—should work. Some operating systems bring out the “animal spirits” on the part of capitalists prompting the need for reformations that better harness and encourage their “better angels.” The chapter concludes that while there are indeed enduring lessons that can and must be carried forward into our own time, the scale and scope of the third capitalist reformation is like nothing that has come before: never before has the capitalist system actually threatened the very environment and climate system that underpins its existence.

The second section of the book then applies these learnings to the corporate transformations—innovations in strategy, organization, and governance—that will be needed to realize the next capitalist reformation. In Chapter 4, “The Great Race,” I expound upon the unique and daunting challenges we now face in redressing the ravages of our current reality: shareholder capitalism. While we have made incremental progress over the past forty years with so-called “win-win” strategies, the challenges we now face—the climate crisis, environmental degradation, toxic inequality, structural racism—present existential threats: we have run out of “on-ramp” and there is no time to waste. I argue that in essence, we are in a race against time. Will a new sustainable and inclusive form of capitalism overtake and make obsolete the extractive and inequitable shareholder capitalism that has ruled the world for the past forty years? The next decade will decide the question. The fate of humanity—and other vulnerable forms of life on Earth—hang in the balance. Drawing upon the Sustainable Development Goals, I coalesce the myriad issues we face into three overarching grand challenges for the world in the decades ahead.

First, we must alleviate extreme poverty in the developing world, by enabling a truly sustainable and regenerative form of rural and agricultural development, one that simultaneously raises incomes, slows urban migration, and averts environmental meltdown; second, we must reverse rising inequality and discontent among those left behind by deindustrialization in the developed world by vanquishing racism and creating a truly inclusive economy, one based on next-generation, inherently clean and regenerative technology. Addressing these first two challenges is prerequisite to successfully confronting the third: an exploding urban population fueled by rural people migrating to megacities around the world in search of a better life and livelihood—a population that could exceed five billion by 2030. These three sustainability challenges provide companies with potential “North Stars” to help focus their quests for purpose and provide fertile ground for prioritizing strategy and investment in the years ahead.

Chapter 5, “Re-Embedding Purpose,” focuses on the importance of making societal purpose core to the DNA of business. It is high time that we move beyond the tendency for companies to “purpose wash” by claiming lofty societal aspirations and sustainability goals while failing to integrate them into core strategy and operations. Given the scale and scope of the challenges we face in the decade ahead, nothing less than transformative change by companies will suffice. Drawing from several company examples based upon my own research, I develop a framework that distinguishes among what I call Foundational (sustainability) Goals, Business Aspirations, and Corporate Quests. On the basis of my personal experience in working with Griffith Foods to embed purpose, I propose a practical approach for developing an integrated set of Foundational Goals, Aspirations, and Quests that truly bring purpose to life; this approach provides the much needed “connective tissue” between lofty purpose and operating reality to translate Purpose into business strategy, operating plans, and metrics.

Chapter 6, “Redesigning the Corporate Architecture” then sketches the new corporate organization that will be required if we are to successfully embed purpose and effectively confront the social and environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. We examine the elements of this architecture—captured by the metaphor of a “House”—by exploring the “next practice” innovations of several leading-edge companies pushing the envelope in this regard. What these innovators reveal is just how important it is to engage the entire organization in the transformation process, integrating the new purpose and strategies into the systems and culture of the organization. I then tell the story of one company’s transformation from a conventional primary aluminum producer to a mission-driven company focused on circularity and sustainability—the transformation from Alcan to Novelis. This story is based on my experience serving as a member of the company’s corporate sustainability advisory council (SAC) during the transformation process.

As important as corporate transformation will be for the third capitalist reformation, it will still prove woefully inadequate so long as the larger systems supporting and defining capitalism—policy regimes, market infrastructure, educational institutions—are badly misaligned. We are now past the point where we can meet the moment through the actions of individual companies alone—even if they are transformational in nature. While the sustainable business movement of the past thirty years, including new corporate forms such as B Corps, have been valiant and important, they are destined to fail by themselves: it’s a bit like arming soldiers with innovative new clubs but still asking them to attack a machine gun nest. They learn quickly to hunker down—or get mowed down. The time has come for business leaders to step up to the role of catalyst for system and institutional redesign. Indeed, a recent Harvard Business School study on the state of capitalism makes clear that government alone cannot solve these problems; business must step up to the plate.14

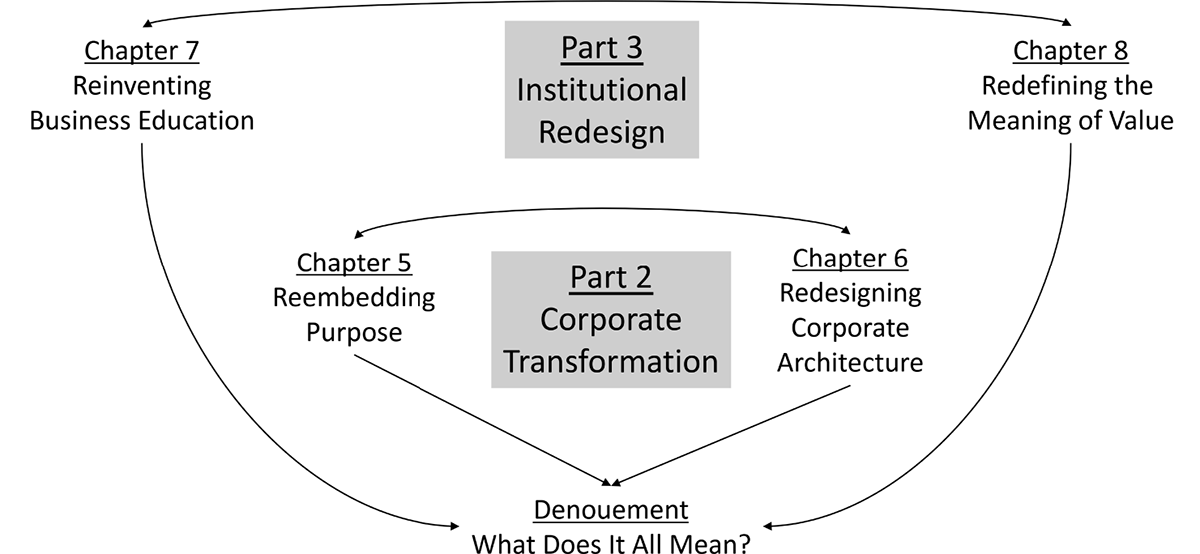

Companies have indeed become increasingly engaged with societal issues (for example, deforestation, inequality) and policies (such as carbon pricing, reform of subsidy regimes). I argue, however, that the root causes (and real leverage points) for dealing with our predicament reside at the institutional level—those systems which underpin, define, and enable the capitalist endeavor itself. History teaches us that institutional change will be crucial if companies—and capitalism—are to realize their full potential as agents of positive change in the future.15 Institutions designed on principles of selfishness and greed favor winner-take-all economies and companies motivated by short-term financial gain. We thus face a structural crisis of the financialized form of capitalism that has dominated for the past forty years. We will need to overhaul virtually every institution from education to finance—B-Schools to Bourses—if we are to realize the deep change that is required—a new operating system and objective function for capitalism and redefinition of the very meaning of value itself. The third section of this book therefore addresses these two key institutional redesigns and the role that business must play if we are to fully realize the next capitalist reformation (Exhibit P.2).

Chapter 7, “Reinventing Business Education,” focuses on the imperative of transforming business education if we are to effectively confront the challenges we face in the twenty-first century. For the past four decades, business schools have been churning out millions of graduates who go on to leadership roles in big banks, investment firms, hedge funds, corporations, and consulting firms—the actors that have perpetrated shareholder capitalism on the world and subjugated the world’s companies with short-termism and shareholder primacy. If we are to realize the next capitalist reformation, we must address this key root cause of our current crisis.

We must return business education to its roots: an institution dedicated to developing leaders with a set of professional ethics and a commitment to the common good, with business as the instrument. We must exorcise the demons of shareholder primacy and market fundamentalism from our business schools if we are to develop a new generation of business leaders with a different perspective about the role of business in the world. After providing a sense of the historical evolution of business education over the past century plus, I suggest how companies and business leaders can and must become champions of business education reinvention. I recount my experience in helping to build a completely new business program at the University of Vermont—the Sustainable Innovation MBA program (SI-MBA). At Vermont, we had the rare opportunity to start with a “clean sheet” and develop a new program from scratch with different DNA, which we believe provides a model for what business education needs to become in the years ahead.

In Chapter 8, “Redefining the Meaning of Value,” I argue that the time has come for business to fundamentally change the narrative regarding the roles of government and finance. Historically, government has played a central role in propelling countries—particularly the US—to new levels of technological progress and prosperity. The time is now to reverse the neoliberal myth that has plagued us for the past forty years: that government is the problem. Making this change will require a renewed willingness on the part of CEOs and business leaders to become outspoken advocates for paying taxes, elevating government, passing policy reforms, and making the public investments needed to accelerate the next capitalist reformation since time is now of the essence.

It is especially important that business leaders advocate for and enable the reinvention of the financial infrastructure that supports capitalism. The objective function of the enterprise system must be refocused on the creation of societal benefit as the driver of shareholder value, not the other way around. Corporate purpose is important, but as Louis Brandeis famously noted over a century ago, the real question is, What is the purpose of the economy? Is it simply growth, shareholder value, and low consumer prices at any cost? Or should healthy market economies be designed to maximize the well-being of everyone and the sustainability of the underlying environment upon which all economic activity depends? The time has come to put the horse back in front of the cart. The creation of long-term, societal value should drive stock price, not short-term profits. Ending the age of shareholder primacy is the audacious goal of the recently launched Long-Term Stock Exchange (LTSE). Much like the SI-MBA, I tell the story of how the LTSE seeks to disrupt and creatively destroy the current public equity market system and replace it with one more in line with a truly sustainable world.

Finally, in the Denouement, I attempt to bring all the strands and elements of the preceding chapters together. I observe that we are at a critical juncture in human history, one where “market fundamentalism” achieved near religious status but left a hole in peoples’ hearts—and pocketbooks. Humans need myth and meaning in their lives, but modern capitalist society has marginalized everything that was once sacred. I argue that sustainability and the emergence of sustainable capitalism might just represent the new story—the myth—that people so desperately need. To make this new story take root, however we also need a new operating system for business and capitalism itself. The final section of the Denouement puts forward the elements of such a new operating system: a set of principles and an integrative framework—“The Sustainable Capitalism Framework”—that pull together all the learnings and lessons from this book.

1. Gale Christianson, Isaac Newton (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

2. William Federer, “Great Plague of London and Sir Isaac Newton,” The Patriot Post, 2020, https://patriotpost.us/.

3. No, I am not comparing myself to Sir Isaac Newton here. Read on!

4. Willis Harmon, Global Mind Change (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1998).

5. Marjorie Kelly, The Divine Right of Capital (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2003).

6. Carl Jung, “Symbols of Transformation,” in: Collected Works, 5, 2nd ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1956).

7. My thanks to Jed Emerson, and his book The Purpose of Capital (San Francisco: Blended Value Press, 2018) for this wonderful metaphor.

8. Business Roundtable Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation, 2019, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans; Davos Manifesto, 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/why-we-need-the-davos-manifesto-for-better-kind-of-capitalism/

9. See Vivek Ramaswamy, Woke, Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam (New York: Center Street, 2021).

10. John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: MacMillan, 1936).

11. Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, Washington, DC, March 4, 1861.

12. Ed Chambliss, A One-Legged Stool: How Shareholder Primacy Has Broken Business (New York: Best Friend Brands, 2022).

13. R. Edward Freeman, Kirsten Martin, and Bidham Parmar, The Power of AND: Responsible Business Without Trade-Offs (New York: Columbia Business School Publishing, 2020).

14. Joseph Bower, Herman Leonard, and Lynn Payne, Capitalism at Risk: How Business Can Lead (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2020).

15. David Kotz, The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017).